Cyber Security Network Attacks

Network Attacks

Attacks on protocols and applications hosted on the Network are plentiful. Web Applications are covered in its own section in this course.

Services can have inherent bugs in them allowing them to be exploited by attackers. These attacks typically involve using special instructions to the Operating System, via the vulnerable service, to take control of the process operating the network service. Buffer Overflows is a category of such attacks.

A network typically holds many applications, some which holds simple logins and others with complex functionality. One way to gain an overview of the attack surface, and also map out easy to exploit vulnerabilities, is to port scan all the assets in the target environment, then screenshot them.

Tools like EyeWitness (https://github.com/FortyNorthSecurity/EyeWitness) accomplish this. The tool allows us to quickly get an overview of which assets are represented on the network, then provides screenshots of each service. By having the screenshots we can easily look and assess quickly which systems we should take a closer look at.

Exploiting a service means to abuse the service in ways it was not intended to. Often this exploitation activity means the attackers are capable of running their own code, this is called RCE ("Remote Code Execution").

Buffer Overflow

Exploitation of network services sometimes involve abusing memory management functions of an application. Memory management? Yes, applications need to move around data within the computers memory in order to make the application work. When programming languages give the developer control of memory, problems like Buffer Overflow might exist. There exists many similar vulnerabilities, and in this section we review Buffer Overflows.

Programming language C and C++ allows developers very much control of how memory is managed. This is ideal for applications which requires developers to program very closely to the hardware, but opens up for vulnerabilities. Programming languages like Java, JavaScript, C#, Ruby, Python and others does not easily allow developers to make these mistakes, making Buffer Overflows less likely in applications written in these languages.

Buffer Overflows happen when un-sanitized input is placed into variables. These variables are represented on the Operating System via a memory structure called a Stack. The attacker can then overwrite a portion of the stack called the Return Pointer.

The Return Pointer decides where the CPU ("Central Processing Unit") should execute code next. The CPU simply controls which instructions the system should perform at any given moment. The return pointer is simply an address in memory where execution should happen. The CPU must always be told where to execute code, and this is what the return pointer allows it to do.

When attacker is able to control the Return Pointer, it means the attacker can control which instructions the CPU should execute!

For example consider the following code C example (do not worry, you do not have to be a C developer, but do your best to try understand what this simple application does):

#include <string.h>

void storeName (char *input) {

char name[12];

strcpy(name, input);

}

int main (int argc, char **argv) {

storeName(argv[1]);

return 0;

}

In many programming languages, including C, the application starts within a function called main. This is indicated in the code above where it says int main (int argc, char **argv) {. Inside the curly brackets { and } the program simply runs a function called storeName(argv[1]);. This will simply accept whatever the user has typed into the program and provides it to the storeName function.

The application has 11 lines of code, but focus your attention on the line that reads strcpy(name, input);. This is a function which tries to copy text from input into the variable called name. Name can hold maximum 12 characters as indicated by the line saying char name[12];. Is there any place in the code that prevents the name supplied being longer than 12 characters? The name variable is supplied by the user whom is using the application and is passed directly into the storeName function.

In this application there is no cleaning or sanitization, making sure the length of the inputs are what the application expects. Anyone running the program can easily input a value larger than what the name variable can hold as a maximum. The name variable holds 12 characters, but what happens when the CPU is told to write more than 12 characters? It will simply perform what is has been told to, overwriting as much memory as it needs to!

When a larger than expected value is attempted written, the CPU will still attempt to write this value into memory. This effectively causes the CPU to overwrite other things in-memory, for example the Return Pointer allowing attackers to control the CPU. Again, if the attacker can overwrite and control the Return Pointer, the attacker controls which code the CPU should execute.

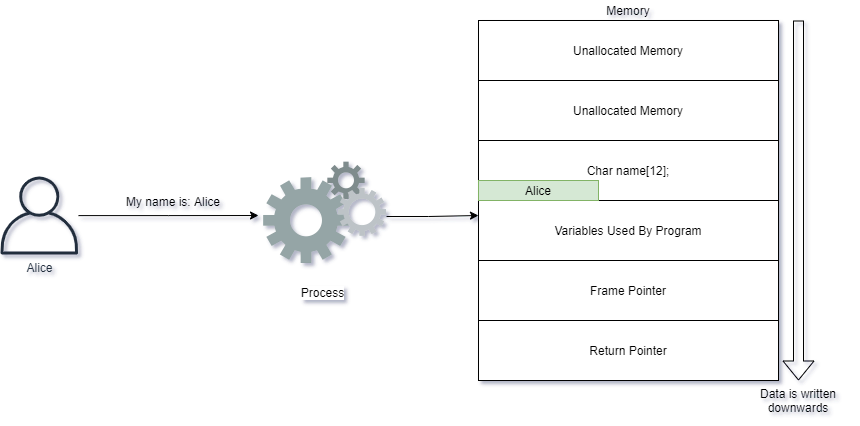

A graphical example shows Alice writing her name into the application we used in the example above:

Alice behaves nicely and provides a name which causes the application to behave as it should. She provides her name Alice and it is simply written into the applications memory.

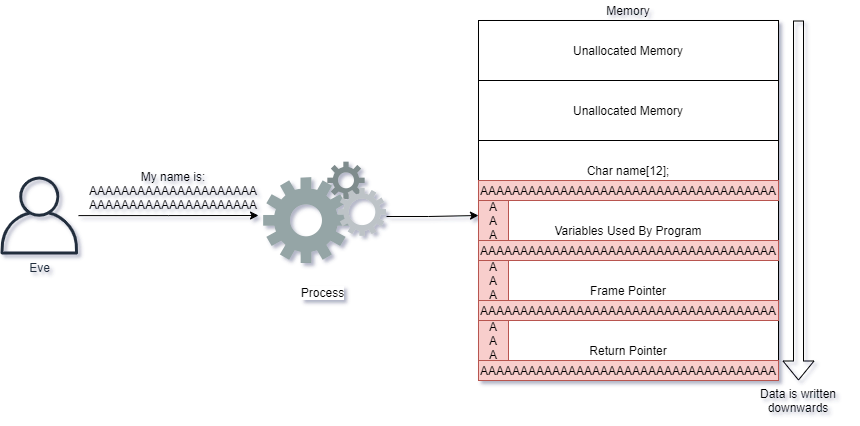

Eve however sends too many characters into the application. What happens then? The CPU effectively takes her input and writes the input into memory, also overwriting other values that exists!

Eve's input caused the CPU to write much more data than what the application expected, and it caused the return pointer to be overwritten. When the CPU tries to execute the next instruction, it is now told to execute code at the location of AAAAAAA...

If Eve were to take control of this server, instead of writing A's, she would instead have to provide code that the CPU can understand into the memory. Next she would make the return pointer have a value which tells the CPU to execute Eve's own CPU code.

Vulnerability Scanners

A vulnerability scanner looks for common vulnerabilities in software and configurations across the network, automatically. It is not designed to find new classes of vulnerabilities, but instead uses a list of pre-defined plugins (or modules) to scan services for issues and vulnerabilities. It does not necessarily hunt for zero-day vulnerabilities! A zero-day vulnerability is a brand new vulnerability which is previously unknown to the vendor of the software and the defenders; for a zero-day vulnerability there currently exists no known patches for the problem.

The scanners have network mapping and port scanning features, including ways to explore and find vulnerabilities in the different applications it encounters.

A vulnerability scanner often supports configuration with credentials, allowing it to log onto systems and assess vulnerabilities instead of finding them from an unauthenticated perspective.

Code Execution

When attackers have found a vulnerability which they are capable of exploiting, they need to decide on what payload they want to run. The payload is the code the attacker wants to have delivered through an exploit.

There are many different payloads an attacker can decide to use, here are some examples:

- Make the victim register with a C2 ("Command and Control") server accepting commands from attackers

- Create a new backdoor user account on the system so the attacker can use it later

- Open a GUI ("Graphical User Interface") with the victim so the attacker can remotely control it

- Receive a command line terminal, a shell, which attacker can send commands through

A payload common by attackers is a bind-shell. It causes the victim to listen on a port, and when the attacker connects they receive a shell.

Firewalls are helpful in preventing attackers from connecting to victims. A firewall would effectively deny incoming connections to the victim as long as the port is not allowed. Only one application can listen on a port, so attackers can not listen on ports that are already in use unless they disable that service.

To circumvent this defensive measure, attackers will instead try make the victim connect to the attacker, making the victim serve up access to the payload. Many firewalls unfortunately are not configured to deny egress traffic, making this attack very viable for attackers.

In this example we see an attacker using a reverse-shell to make the victim connect to the attacker.

Network Monitoring

Attackers require the network in most cases to remotely control a target. When attackers are capable of remotely controlling a target, this is done via a Command and Control channel, often called C&C or C2.

There exists compromises via malware which is pre-programmed with payloads which does not need C2. This kind of malware is capable of compromising even air-gapped networks.

Detecting compromises can often be done via finding the C2 channel. C2 can take any form, for example:

- Using HTTPS to communicate to attacker servers. This makes the C2 look like network browsing

- Using Social Networks to post and read messages automatically

- Systems like Google Docs to add and edit commands to victims

![]()

Only an attackers ingenuity sets the limit for C2. When considering how to stop attackers with clever C2 channels, we must often rely on detecting statistical anomalies and discrepancies on the network. For example network monitoring tools can detect:

- long connections used by C2, but which is unnatural for the protocol in question. HTTP is one of those protocols where it is not very common to have long connections, but an attacker using it for remote control might.

- Beacons used by C2 to indicate the victim is alive and ready for commands. Beacons are used by many kinds of software, not just attackers, but knowing which beacons exists and which you expect is good practice.

- Strobes of data suddenly bursting from the network. This might indicate a large upload from an application, or an attacker stealing data. Try understand which application and user is causing strobes of data happening and apply context to it. Is it normal or not?

There exists many ways defenders can try to find anomalies. These anomalies should be further correlated with data from the source system sending the data.

For network monitoring, context should be applied to help determine noise from signal. That means that a SOC ("Security Operations Center") should try to enrich data, for example Source and Destination IP Addresses with context to help make the data more valuable.

Applying context can be described with the following scenario: An attack arrives from the Internet but it tries to exploit a Linux vulnerability against a Windows service. This would typically be considered as noise and could safely be ignored; unless, what if the IP address doing the attack is an IP address from your own network or a provider whom you trust? The context which we can apply can then provide valuable insight into us exploring the attack further. After all, we don't want systems we trust launching any attacks!

Peer to peer traffic

Most networks are configured in a client to server fashion. Client access the servers for information, and when clients need to interact with one another they typically do it via a server.

An attacker however will likely want to use peer-to-peer, i.e. client to client, communications to leverage low hanging fruits like re-using credentials or exploiting weak or vulnerable clients.

For example port 445, used by SMB, is a good indicator to use for detecting compromise. Clients should not be talking to one another via SMB in most environments, however during a compromise it is likely an attacker will try use SMB to further compromise systems.

Lateral Movement and Pivoting

Once a system is compromised, an attacker can leverage that system to explore additional networks the compromised system has access to. This would be possible in an environment where a compromised system has more privileges through the firewall, or the system has access to other networks through e.g. an additional network card.

Pivoting means an attacker uses a compromised host to reach into other networks. An illustration of this is shown here where Eve has compromised one system and is using it to scan and discover others:

Lateral Movement is the act of taking advantage of the pivot and exploit another system using the pivot. This new system can now be further used to do pivoting and more lateral movement. Eve in this example uses Server X to further discover System B.